Rhythm is fluid. Start on any beat, end on any beat.

Meter and form impose order over rhythm. It restrains rhythm, controls it. Without these structures in place, our music can become chaotic. This can be fun at times but we want to learn to play well with others.

Working within a musical form, we can manipulate time and free ourselves from formulaic handcuffs by altering our Starting Points and Resolution Points ultimately displacing the beat and moving towards polymeter.

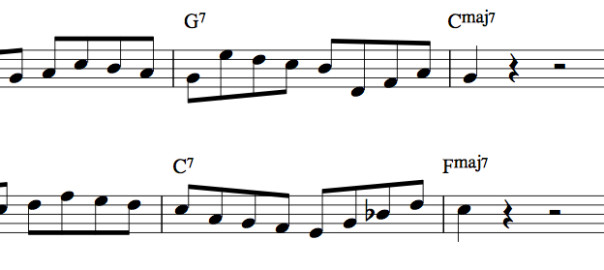

Let’s start with a simple ii V I phrase.

Starting Points

Music can start on any beat. Beginning on beat one is obvious, simple. Effective but predictable. We should create lines which begin on (or off) any beat. Let’s take the previous phrase in its entirety and start it on different beats:

By keeping the lick itself identical but changing the starting point we have displaced the beat.

By keeping the lick itself identical but changing the starting point we have displaced the beat.

The first lick no emphasizes beat two courtesy of our starting point, resolution and the ascending 6th in the second bar. The second lick places similar emphasis on beat 4. Also notice how both examples now displace the harmonic emphasis of the line. The first creates a suspension on beat one of measure three. The second lick anticipates both the Gm7 in measure 12 and somewhat less obviously the Fmaj7 in measure 14.

Ending Points

Starting on different beats allowed us to alter the rhythmic and harmonic structure of our phrase without changing our lick one note. Shortening or extending our phrase at different points will put the emphasis on different beats. With very small alterations we can change our resolution point creating all kinds of harmonic variety.

Shortened:

Here we have shortened each of or our original phrases by removing one beat. In the first lick I’ve also changed the final note to create a more pleasing resolution. Note that we can shorten the first half (ii chord), second half (V chord) or both. Measure 18 emphasizes beat four, measure 22 emphasizes both beats two and four. Both licks now end with an anticipation.

Here we have shortened each of or our original phrases by removing one beat. In the first lick I’ve also changed the final note to create a more pleasing resolution. Note that we can shorten the first half (ii chord), second half (V chord) or both. Measure 18 emphasizes beat four, measure 22 emphasizes both beats two and four. Both licks now end with an anticipation.

Extended:

We can extend the lick just the same as we can shorten it: by strategically adding notes. Employ your diatonic and chromatic surrounds, passing and neighbor tones. Again we can extend the phrase at any point. Measure 27 emphasizes beat two, m. 30 beat four and m. 31 beat two. As shortening the licks created harmonic anticipation, extending them creates a suspended resolution.

We can extend the lick just the same as we can shorten it: by strategically adding notes. Employ your diatonic and chromatic surrounds, passing and neighbor tones. Again we can extend the phrase at any point. Measure 27 emphasizes beat two, m. 30 beat four and m. 31 beat two. As shortening the licks created harmonic anticipation, extending them creates a suspended resolution.

Putting It All Together:

None of these devises are exclusive: We can displace our starting point, shorten or extend our phrases. In the first lick above, I have both started the phrase on beat two and shortened the phrase by one beat placing additional emphasis on beat two while returning our resolution to beat one of the third measure.

None of these devises are exclusive: We can displace our starting point, shorten or extend our phrases. In the first lick above, I have both started the phrase on beat two and shortened the phrase by one beat placing additional emphasis on beat two while returning our resolution to beat one of the third measure.

The second lick starts on beat four, shortens the lick (m. 18 beat 2) and extends the lick (m. 39 beat 1). In m. 37 we emphasize beat four, m. 18 beat two and m. 39 beats two and four. Resolution has been delayed by a full three beats and the lick sounds very different from the original.

Summary:

Changing our starting and resolution point, shortening or extending the phrase; these are all ways to generate rhythmic variety and add some spice to our playing. Changing the rhythmic emphasis, suspending or anticipating the harmonic changes can help us break down the bar line. Mixing and matching these techniques will help you quickly expand your melodic vocabulary.

Taking It A Step Further:

Take a look at the shortened and extended phrases. When we shorten a four-beat phrase we end up with a three-beat phrase. If we do this repeatedly we end up in 3/4 time.

Playing a 3/4 phrase in a 4/4 is polymeter. Two (or more) meters competing with one another is a wonderful way to generate tension and mystery. Just be sure to keep track of where beat one is!

Playing a 3/4 phrase in a 4/4 is polymeter. Two (or more) meters competing with one another is a wonderful way to generate tension and mystery. Just be sure to keep track of where beat one is!

One more thing, extending our four-beat phrase creates a five-beat phrase

Extending (or shortening) a phrase can be a great tool for learning to play in less familiar time signatures such as 5/4 & 7/4.

Extending (or shortening) a phrase can be a great tool for learning to play in less familiar time signatures such as 5/4 & 7/4.